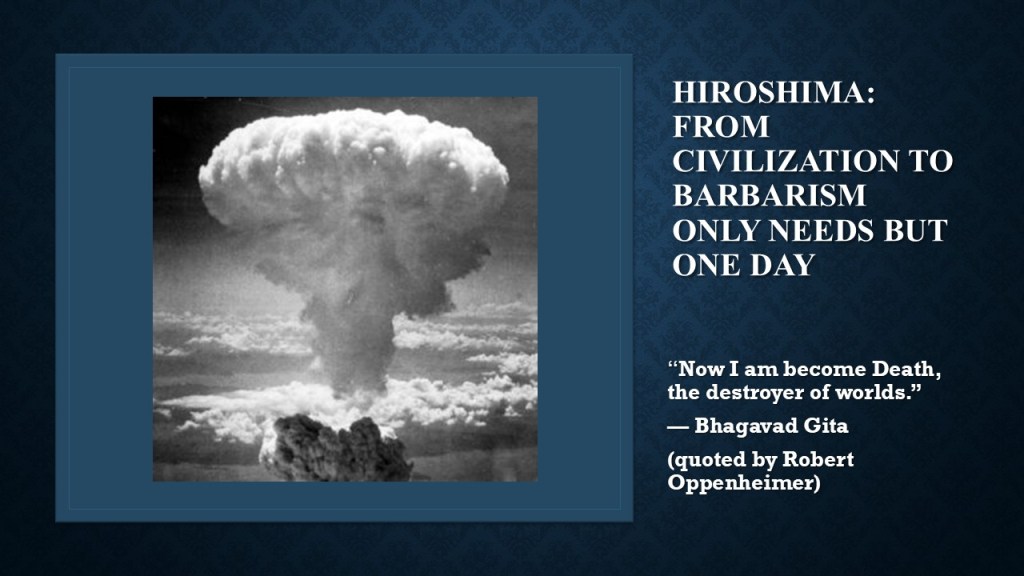

HIROSHIMA: From Civilization to Barbarism Only Needs but One Day

As the historian Will Durant, author of “The Story of Civilization” writes

“From barbarism to civilization requires a century;

from civilization to barbarism needs but one day.”

Will Durant

Heraclitus decries, war as “The father of all things” and even Voltaire follows this line: “Famine, plague and war are the three most famous ingredients of this wretched world.. All animals are perpetually at war with each other.. Air, earth, and water are arenas of destruction.”

In war, there is a conflict between opposing forces and principles. Nevertheless, a distinction must be made between the targeting of military and civilians, as well as justifiable targets, strategies, and the use of weapons. However, war is not based on the chivalric code of the 12th century; it is uniquely terrifying and inevitably destructive, with civilians as the main victims. This is despite the prohibition of targeting civilians in Article 25 of the 1899 Hague Conventions and the 1907 Hague Convention, which states, “the attack or bombardments, by whatever means, of towns, villages, dwellings, or buildings which are undefended is prohibited.”

Although moral values play a role in international relations and war (just war theory), the best international humanitarian and armed conflict law can do is set limits. When the beasts of war are unleashed, they are like barbarians at the gate, and morals become a luxury. In international relations and conflict, the book of ethics shows itself to be a very thin book.

The great war, WWII (1939–1945), the most destructive war ever seen, was a so-called moral war, a “total war,” leading to the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians. In the Holocaust, six million Jews were killed, and the war took more than 50 million lives and wounded hundreds of millions. A total war that took more lives of civilians than combatants, a war without restraint in warfare in which moral responsibility becomes problematic. A war in which the defenders of the light in the pursuit of defeating the followers of the darkness used the same brutal and vicious tactics is a testament to this.

Prior to the war, the American State Department declared “civilian bombings are in violation of the most elementary principles of those standards of human conduct which have been an essential part of civilization.” President Franklin D. Roosevelt spoke to the issue in 1939, as well calling civilian bombing “inhuman barbarism.”

Without minimizing the ruthlessness of Germany and Japan, these words spoken about the standards of human conduct sound hollow. This is confirmed by Britain and America’s shift in policy from respecting the rights of innocent civilians to specifically targeting civilians. In war, humanity is shown a mirror of the monstrosity of war and the thin layer covering our civilization, evidenced by the erosion of moral values that govern our world society.

Until 1944, American officers recognized the value of the principle that civilian populations should not be targeted for bombing. They were very wary of the ethical problems resulting from indiscriminate bombing of civilians and pursued a “tactical” or “precision” bombing doctrine, targeting exclusively German military and industrial facilities and not bombing entire urban “areas.”

In 1945, the Americans extended their policies of targeting innocent civilians to the cities of Japan. The US continued to drop incendiary bombs filled with phosphorus (later napalm) on innocent Japanese women and children. This continued even when Japan was close to surrendering, using atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, leading to the surrender of Japan.

The bombing of civilians deserves more introspection by all, and these events should not be erased from our memory like strangers passing in the night. We should conclude the bombings on Dresden, Hamburg, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Tokyo should be considered a war crime.

This also begs the questions about the atomic bombings, and about the intentional attack on the civilian population of Nagasaki and Hiroshima:

When is the deliberate mass murder of civilians on this huge scale ever justified?”

“What makes a decision a war crime and immoral if you lose, and not a war crime and not immoral if you win a war?”

For the last almost eighty years, there have been different views about the ethical implications and moral justification of dropping the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which ended the great war. There are no easy answers to this complex dilemma—the difficult balance between national interests, public demands for vengeance and retribution, and ethical values. Some of those who made the decision struggled with the decision and were troubled, even tormented, about the ethical implications, and the ghosts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are still with us today.

The enormity of the atomic bombings on the civilian population of Hiroshima and Nagasaki give reason for pause and actually confirms the underlying nature of and man’s barbarity. Man’ s capacity to think was overwhelmed with the abandonment of moral constraints and reason, resulting from moral and political degeneration.

What remains is to conclude, the “mini supernova’s” which turned the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki into powder and blocked the sunrays, triggered the indiscriminate and colossal mass murder of civilians. At least 200,000 people were killed by the flashes, firestorms, and radiation; tens of thousands more injured; an unquantifiable inter-generational legacy of radiation, cancer, and trauma. (4)

Visiting Nagasaki Genbaku Shiryōkan, Heiwa Koen, and the Dome in Hiroshima, one can only reach the conclusion that the use of nuclear weapons is monstruous, inexcusable and by using this Frankenstein weapon the United States signalled to the world that it considered nuclear weapons to be legitimate weapons of war.

The next time the nuclear weapons were almost used was during the Korean war when General MacArthur, the commanding officer, demanded authority to use nuclear weapons against Chinese targets. In April 1951, President Truman transferred nine nuclear bombs to US military control, but Truman held back on its use given his matured views in the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Between 1945 and the USSR’s first detonation of a nuclear device in 1949, different pre-emptive nuclear scenarios were formulated against the former Soviet Union, what Winston Churchill called the Russian problem. This led to the development of The Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP), a plan prepared in 1960 for nuclear war, which essence was a massive nuclear strike on military and urban-industrial targets in the Soviet Union, China, and their allies.

The attack on December 7, 1941, by the Imperial Japanese Navy, bombing warships and military targets in Pearl Harbor, is the classic case of how world states react when matters of vital security are perceived to be at play. They will do whatever they think is in their military and economic self-interest. At a time when the US was shifting from military force to economic power, this serves as a powerful lesson about underestimating the adversary. When imposing sanctions, the greater the pressure of the sanctions is for the rival, the greater the need, in the name of self-interest, to strike back.

The attack on Pearl Harbor followed a prolonged period of strained relations, with the US progressively imposing economic pressure on Japan, deliberately targeted against Japan’s core interests, caused Japan to choose a military option. The War Plan Orange, first developed in 1890 by the US Navy, with different revisions throughout 1941 provides a revealing insight into the events at Pearl Harbor.

The use of the atomic bomb against Japan, after Japan initiated the war on December 7, was a foregone conclusion and already decided as early as May 5, 1943, by the Military Policy Committee. Earmarking Japan as a target for the nuclear device happened more than two years before on July 16, 1945, the first test was made of the new device, nicknamed “the gadget.” (5) The committee composed of scientist and military officers included Major-General Leslie Groves, (8) head of the Manhattan Project, was set up to determine how best to use nuclear weapons.

In the early spring of 1945, General Leslie Groves established the “Target Committee,” to provide military recommendations on how to use of the atomic bomb and was to determine the best techniques and targets in Japan to produce the most effective military destruction and psychological effects on the Japanese Empire. Their recommendations would become paramount as the Interim Committee made its final decisions. (6)

In May 1945 Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, (7) with the approval of President Harry Truman, established the “Interim Committee” and selected James F Byrnes (9) as Truman’s personal representative. For Byrnes, the decision to use the bomb on Japan had political implications beyond ending the war. Byrnes believed in “atomic diplomacy,” whereby the US could leverage the bomb in post-war negotiations and make Russia “more manageable.”

The Interim Committee selected Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, Kokura Arsenal, and Niigata and in the final analysis made Kyoto and Hiroshima the primary targets of the atomic bomb.

The Target Committee noted that “from the psychological point of view there is the advantage that Kyoto is an intellectual centre for Japan and the people there are more apt to appreciate the significance of such a weapon as the gadget” while Hiroshima was “an important army depot and port of embarkation in the middle of an urban industrial area.”

The identification of Kyoto, chosen because of it seize-one million people- and showing the effect of the bombing met with strong opposition from Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, given its long history as a cultural centre of Japan, the former ancient capital. As Evan Thomas writes “Groves wants to destroy Kyoto for the same reason Stimson wants to protect it -to cut out the cultural heart of Japan.” (14)

For Joseph Grew, former ambassador to Japan, the acting secretary in May 1945, the case was never clear, believing and urging President Truman to abandon the demand for unconditional surrender and instead offer the Japanese terms: principally, in return for surrender, Japan can maintain its emperor. Stimson at the time thinks this would be a mistake to show weakness. As Grew wrote Stimson after the Harper’s article chances were missed and “The bomb might never been used at all” and “the world would have been the gainer.”

As the Nuclear Museum documents confirm at a June 1, 1945, Interim Committee meeting, Byrnes recommended the use of the atomic bomb. Martin Sherwin writes in “A World Destroyed: Hiroshima and the Origins if the Arms Race, “ Byrnes suggested, and the members of the Interim Committee agreed, that the Secretary of War should be advised “the present view of the Committee was that the bomb should be used against Japan as soon as possible; that it be used on a war plant surrounded by workers’ homes without prior warning.”

For Byrnes, the decision to use the bomb not only promised to end the war sooner but also, in his words “might put us in a position to dictate our own terms at the end of the war.”

During the Potsdam conference, (July 17–August 2, 1945), attended by Winston Churchill, Harry Truman, and Joseph Stalin, the participants discussed the substance and procedures of the peace settlements in Europe. Truman informed Stalin about the United States’ “new weapon” (the atomic bomb) that it intended to use against Japan. On July 26, with the Potsdam proclamation an ultimatum was issued to Japan demanding unconditional surrender and threatening “complete and utter destruction” otherwise.

After Japan rejected this ultimatum, the United States, without much “mature consideration” as originally agreed in the signed agreement between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

There are different schools of thought on this issue. For some the attack over the centre of Hiroshima and three days later of Nagasaki was necessary to end the war quickly, especially when Japan and the armed forces were unwilling to accept unconditional surrender given the offered conditions, which conditions regarding Emperor Hirohito were later revised in such a manner that Emperor Hirohito would not be subject to a war crimes trial and remained a figure head “subject to” the Supreme Allied commander as confirmed on August 11, 1945.

Others, so called “revisionists,” like the undersigned, are ridiculed for not joining the choir of self-righteousness but cannot ignore a sense of revulsion and contend that dropping the bombs by the U.S. on the civilian population of Hiroshima and three days later Nagasaki was immoral, unethical, unnecessary and an act of barbarism with tones of racial prejudice, an act that could and should have been avoided at all costs.

Despite claims Japan’s surrender was caused by the dropping of the atomic bombs, Japan’s surrender was most likely more influenced by Russia entry into the war, two days after the bombing of Hiroshima, and the Russian invasion into Manchuria, that moved Japan towards surrendering.

This is the conclusion McGeorge “Mac” Bundy, who served as National Security Advisor to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, reaches in his 1988 book “Danger and Survival”, “Hiroshima alone was enough to bring the Russians in; these two events together brought the crucial imperial decision for surrender, just before the second bomb was dropped.”(10)

However, this horrific event, has not given much cause to reflection or a moral awakening in the United States and has its reasoned defenders, who still follow the framing of this decision by the U.S. Government, with Hiroshima and Nagasaki as an unfortunate but necessary act for the greater good.

When Truman broadcasted the bombing of Hiroshima to the nation, the public at large was deceived by announcing that Hiroshima was a military base, claiming this target was chosen to avoid the killing of civilians, but the facts contradict this. Hiroshima had modest military value but was targeted for psychological effect as the target committee early 1945 has recommended. President Truman outlined the prospect for Japan

“If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth…. “

Harry Truman

Failing to receive the demanded response of unconditional surrender, the United States rushed to drop the atomic bomb on August 9th, 1945, on Nagasaki. On August 15th, Japan surrendered and remained occupied until 1952.

As Jonathan Rauch wrote in the 2002 July issue of the Atlantic in “Firebombs Over Tokyo.” “The much harder question is why the United States rushed—and it did rush—to bomb Nagasaki only three days later. Neither President Harry Truman nor anyone since has provided a compelling answer.”

After the bombings, the American public was kept fairly ignorant about the conditions in the two major cities which were, like the whole of Japan under military censorship. The public was misled about the radioactive effects and how this decimated the largely civilian population of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in excruciating ways.

General Groves never had or showed any moral qualms and testified before the Special Senate Committee on Atomic Energy, ignoring, discounting, and denying the reports about the radiation effects. The testimony of Phillip Morrison, a scientist of the Manhattan project contradicted at the end of 1945, clarifying the facts about the radiation effects to the same committee.

It was not until one year later, after the full issue of The New Yorker landmark august 1946 report “Hiroshima” was published, dedicated to the bombing and its aftermath, written by John Hersey, that the public was informed about the realities of the destruction and suffering. Hersey gave a firsthand account and showed the bombing through six pairs of eyes of survivors: two doctors, two women, a Protestant clergyman, and a German Jesuit priest. (11)

The piece’s impact was strong and immediate and not universally positive. Parts of it were excerpted in newspapers around the world, and it was read, in its entirety, on the radio, raising questions about the use of such a horrific weapon. “Were we war criminals for having done this?”

After the publication, General McArthur occupation forces in Japan quickly organized to suppress additional such reporting. In his article in the February 1947 issue of Harper’s Magazine (12), Secretary of War Henry Stimson provided the American public with his rationale for using the atomic bombs, “The principal political, social, and military objective of the United States in the summer of 1945 was the prompt and complete surrender of Japan.” (7)

Henry Stimson, who himself had moral reservation about the use of the Atomic Bomb and what he viewed as unethical war practices of merciless attacks on civilians, was a reluctant participant in the use of the bomb on Japanese cities. Despite his ethical objections, Stimson responded in defence to growing criticism of the use of the atomic bombs.

The Japanese philosopher Masahiro Morioka says Simpson’s reasoning can be seen as the utilitarian “greater good” argument that the bombing prevented a greater degree of human suffering. Although the victims mostly women, children, and elderly might disagree with this argument. (13)

This case, how to justify the indefensible, is also supported in Evan Thomas’s recent book, “The Road to Surrender (8),” in which an account is given of the last days of the Second World War, as American and Japanese leaders were confronted with the reality of the atomic bomb.

In the summer of 1945, Germany had surrendered to the Allies while Japan was largely defeated. Thomas focuses on Henry Stimson, the U.S. Secretary of War, U.S. General “Toomey” Spaatz, and Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo. The book, although interesting, shows the dilemmas in the final days of the war well and supports the American narrative that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was a justified price to pay for the surrender of Japan.

Evan Thomas rejects the guilt and anxiety felt by Henry Stimson for dropping the atomic bombs with a categorical No, given the long shadow of the Japanese military on the decision-making process. This is a view that can be taken, but the validity of this supposition will never be known. With this reasoning and justification for the deliberate detonation of the atomic bomb over the residential and commercial city of Hiroshima, resulting in the mass murder of civilians, Evan Thomas is not taking us forward to a more enlightened society but is taking us back to the stone age. This understanding ignores the perspective of a considerable number of top contemporary military leaders, that the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was not a matter of military necessity.

Japan was already on the brink of collapse; it was running out of steel, food and oil and had no allies; its navy was almost destroyed; its islands were under a naval blockade; and its cities were undergoing concentrated terror air attacks, routinely levelling entire Japanese cities, creating self-fuelling firestorms through the combined use of high explosive and incendiary phosphorus- and napalm cluster bombs—for which traditional Japanese homes of wood and bamboo, walled with paper screens and floored with rice straw mats, would be little more than tinder and kindling; the atomic bombing was unnecessary.

–Chester W Nimitz, commander in chief of the US Pacific fleet, insisted that they were “of no material assistance in our war against Japan.”

–General Dwight D Eisenhower, later president, recalled having voiced his grave misgivings based on his beliefs that Japan was already defeated when informed by Secretary of War Henry Stimson that atomic bombs would be dropped on Japan.

–General Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander of the southwest Pacific area, saw “no military justification for the dropping of the bomb.”

–Admiral Willim Leahy, Truman’s chief of staff, wrote in his 1950 memoir, “The use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender… In being the first to use it, we … adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages.”

–Major General, Curtis LeMay, who was tasked in January 1945 with revitalizing the air campaign against Japan with incendiary bombing with napalm and white phosphorus against Japan’s cities and to abandon the policy of precision bombings, would consider the use of atomic weapons unnecessary “We felt that our incendiary bombings had been so successful that Japan would collapse before we invaded.”

This is also the essence of LeMay’s letter to Brig. General Lauris Norstad of April 25, 1945, in which he confirms his belief that Japan can be defeated by bombing alone. As General Lemay later said about the victims of the incendiary bombings “We scorched and boiled and baked to death.”

Although the situation was volatile and difficult at the time, with the Japanese Government and the Supreme Council dominated by the military divided and ruled by fanatism on the question of further resistance, and as Evan Thomas confirms, are considering a coup d’état and a state of emergency, in defiance of the desire of Emperor Hirohito, the “Mikado“ “to terminate the war as quickly as possible.” This at a time, the consensus among Allied members in the military was Japan was close to capitulating. About the internal volatile situation Secretary Stimson was informed, given the interception by the United States of Japanese diplomatic messages. With Stimson still preferring to head off a bloodbath, suggesting to President Truman to offer Japan assurances with Emperor Hirohito permitted a titular role to enable a diplomatic solution.

It was foolish and short-sighted not to seek a diplomatic solution, but this was rejected by James Francis Byrnes, the new Secretary of State, who had the ear of President Truman and by General Groves, who’s committee advocated to dropping the atomic bomb on Japan as early as 1943 and the New Deal hardliners in the US state department who, as Evan Thomas writes

“believe that Japan’s feudal hierarchy needs to be torn out by the roots and replaced by a system that honours the people’s choice.”

US state department new deal hardliners

This form of cultural barbarism favoured by Groves was rejected, but human barbarism, the slaughter of innocent women, children and old men, remained on the agenda.

President Harry S. Truman, sensitive to public opinion, followed the argument and the populist President did not wish to be seen as “an appeaser” by the public, but later accepted the idea of Emperor Hirohito as a figurehead, subject to American supervision, but only after atomic bombs had been dropped and vengeance and retribution from the air had been delivered. Over the years, the nuclear beast, Frankenstein’s monster, has continued to grow and in its continued drift to disaster, with technological advancements made, with uncontrollable “deterrence” and its first use, the world has become infinitely more dangerous with the survival of humanity threatened.

The moral dimensions of nuclear weapons are also explored by the Oxford University philosopher Toby Ord in his book “The Precipice.” (11)

“In the 21st century the explosive power of thermonuclear bombs is so great that they pose an existential risk of triggering a nuclear winter, caused by smoke from firestorms blocking sunlight for years. “Hundreds of millions of direct deaths from the explosions would be followed by billions of deaths from starvation, and – potentially – by the end of humanity itself,” he writes.

“We stand poised on the brink of a future that could be astonishingly vast, and astonishingly valuable,” Ord writes. “Yet our power to destroy ourselves – and all the generations that could follow – is outpacing our wisdom.”

The moral dimensions did not stop President Truman, in the absence of unconditional surrender by Japan, from informing the British government “that sadly, he is preparing to drop a third atom bomb on Tokyo.” In the absence of the unconditional surrender by Japan, preparations were made to produce and supply nine more atomic bombs, contemplating to be used in a barrage against the Japanese armed forces. Just as General Carl Spaatz, the army air forces commander assigned to lead the strategic bombing campaign, understanding the horrific consequences required a written order, but was indifferent to dropping the third bomb on Tokyo, just hours before he learned of Japan’s surrender on August 14th, 1945.

Today, such an order would be in violation with humanitarian principles and the law of armed conflict. In the 21st Century, as Katherine E. McKinney, Scott D. Sagan and Allen S. Weiner write in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientist the “Atomic bombing of Hiroshima would be illegal today,” with the undisputed conclusion, “it would violate three major requirements of the law of armed conflict codified in Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions: the principles of distinction, proportionality, and precaution.” (12) If this would stop future governments from disregarding humanitarian principles and the law of armed conflict in future conflicts is questionable, as the nuclear first strike threats against North Korea and Ukraine, by respectively the United States and Russia show.

However, by using the nuclear weapons in 1945 the atomic genie has been let out of the bottle and the moral dilemmas of the use of nuclear weapons have decreased and the likelihood of the use of nuclear weapons has increased. Secretary of War Stimson recognized how the atomic bomb would influence the future international order and the moral dilemma, affecting the moral standing of the US in the world and how this new gadget would place civilization at enormous risk.

Obviously, President Harry Truman cannot be accused of having much of a moral awakening but was mindful of American public opinion, which wanted unconditional surrender, vengeance and retribution for Pearl Harbor and the Japanese atrocities. Major General Curtis LeMay, the hawkish chief of the XXI Bomber Command, a man who throughout the European theatre as leader of the 305th Bombardment Group in Britain had already proved his willingness to kill civilians by the hundreds of thousands in pursuit of victory, directed the assault over Japan in the final days of the second world war.

The words of Colonel Harry F Cunningham, an intelligence officer of the US Fifth Air Force on July 21,1945, is symptomatic

“The entire population of Japan is a proper military target.

There are no civilians in Japan.”

colonel harry f cunningham

The fact is that with the targeting of civilians, with the intent of killing as many as possible to break morale and to bring an end to the war, was already within the capacity of the U.S. Army / Air Force before the atomic bombs were dropped. General LeMay was remarkably effective with his relentless firebombing campaign and had already scorched more than 60 cities and left only 6 cities standing, until the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Brigadier General Curtis LeMay did not believe in moral constraints, but in the concept of total war and thought any action acceptable in the pursuit of military victory. In general Lemay’s opinion, if bombers attacking Germany could not break the enemy’s ability to fight, they would break its will by the targeting of civilians

“THERE ARE NO INNOCENT CIVILIANS. IT IS THEIR GOVERNMENT AND YOU ARE FIGHTING A PEOPLE, YOU ARE NOT TRYING TO FIGHT AN ARMED FORCE ANYMORE. SO, IT DOESN’T BOTHER ME SO MUCH TO BE KILLING THE SO-CALLED INNOCENT BYSTANDERS.”

brigadier genera; curtis lemay

But the incendiary bombings, unleashing massive firestorms on Tokyo, and on German cities like Dresden, Hamburg, were immoral and disregarded the most basic standards of morality, indiscriminate targeting and killing innocent civilians, women, children, and men. It is hard to see how bombing medieval cities like Wurzburg or Pforzheim, which were without any military significance could contribute to shortening the war in Europe.

As the patrician, Secretary of War Stimson reflects and records in his diary about Dresden “the account out of Germany” makes the destruction “even on its face terrible and probably unnecessary.” After Dresden Stimson, a thoroughly decent person of high moral standing, principled realism, and very much concerned with unethical war practices and civilian casualties had explicitly stated that the United States did not engage in terror bombing of cities. This questioning and the desire of Stimson for an investigation on the Dresden bombings touch on the sensitive issues of civilian bombing, which was not shared by General George C Marshall, the chief of staff of the army or the British Air Marshal Arthur Harris.

As the world moved from Pax Britanica to Pax America, with geo-politics and the American – Russian competition already on the agenda, dropping the bombs on Hiroshima, Nagasaki and possibly Tokyo had also a geo-political strategic purpose and was also meant as a warning towards Russia and China. The large civilian death toll that resulted from the bombings, the psychological effects of the effective military destruction by the United States can be seen as a small price to pay by the United States in return for the assertion of their supremacy on the world stage immediately after the Second World War.

But this had also the effect and led to the arms race, development of the intercontinental bomber; the H-bomb; the ICB Missile; reconnaissance from satellites and space weapons. The conclusion is warranted, given the advances made in nuclear technology and artificial technology with weapons which can make their own judgement, this has brought Armageddon closer than ever before, with weapons which have in the words of Henry Kissinger “the capacity to extinguish humanity in an infinite period.”

This would give any reasonable person pause for thought.

In looking at the aftermath of both world wars. there is an old truth, the victors of war write the history, and WW I justice was decided by the winners at Versailles and for WW II at the war crimes tribunals at Nuremburg and Tokyo. This justice is based on retribution as a punishment that gratifies the public desire for vengeance. This justice has also elements of ex post facto Law.

When General Curtis LeMay reflected years later about the morality, he recognised

“I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal, fortunately, we were on the winning side…. All war is immoral, and if you let it bother you, you are not a good soldier.”

Brigadier General Curtis lemay

Victor’s justice was the logic of the Nuremberg Tribunal, which Trial was criticized for being one-sided, inefficient, ineffective, politicized, very costly and unfair body, where high politics was masquerading as law.

In the words of Harlan Stone, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court who described the proceedings of the Nuremberg Tribunal as a “sanctimonious fraud” and a “high-grade lynching party” to Germans. This was also the logic of the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, where perpetrators of war crimes and crimes against humanity at Hiroshima and Nagasaki pronounced judgment on the war crimes of the defeated.

Although the victors in conflict always write the history, they do not determine the morality and the bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were a most abhorrent act, an act of barbarism, a crime against humanity. With the adoption of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and 1977 Additional protocols, the laws of armed conflict confirm this conclusion.

The U.N. General Assembly in 1961 also recognized that the use of nuclear or thermonuclear weapons constituted “a crime against mankind and civilization.”

Netherlands, William J J Houtzager, Aka WJJH – January 2024

📌 Blog Excerpt

Reflection about the ethical implications and consequences of WW II, focused on the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The declared necessity of the bombings versus their actual value, and the concept of civilian targets in warfare, institutionalized with the Geneva Conventions. There is the paradox of victor’s justice in war tribunals, where war crimes and atrocities committed by victors themselves, such as the atomic bombings, are often overlooked or justified.

References

- Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin – American Prometheus the Triumph and Tragedy of Robert J Oppenheimer (Atlantic Books 2008) ISBN: 978-1-84334-705-1

- Max Hastings, Bomber Command (NY: Dial Press, 1979), ISBN: 978-1-529-04779-0

- Revisiting Morale under the Bombs: The Gender of Affect in Darmstadt, 1942–1945

- Katrin Schreiter, Central European History, Vol. 50, No. 3 (September 2017), pp. 347-374

- Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – 1945 – Nuclear Museum

- The Interim Committee-Nuclear Museum

- Target Committee recommendations May 10 and 11, 1945 – Nuclear Museum

- Profile Henry L Stimson – Secretary of War – Nuclear Museum

- Profile Leslie R Groves – Director Manhattan Project

- Profile James F Byrnes – Secretary of State – Nuclear Museum

- McGeorge Bundy, Danger and Survival: Choices about the Bomb in the First Fifty Years. New York: Vintage Books, 1988. ISBN 0-394-52278-8.

- The New Yorker – John Hersey s – Hiroshima

- The Harper Magazine 1947 Article Henry Stimson

- Masahiro Morioka -The Trolley Problem and the Dropping of The Atomic Bombs

- Evan Thomas – Road to Surrender: Three Men and the Countdown to the End of World War II – – Random House – 2023 – ISBN- 0-399-58925-2

- Toby Ord – The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity – Hachette Books-2020 ISBN:0-316-48491-6

- Bulletin Of The Atomic Scientists – Why the Atomic bombing of Hiroshima would be illegal today

One thought