The Weed in the Garden: On Rob Riemen and the Return of Fascism

✍️ Author’s Note

This reflection engages with Rob Riemen’s urgent warning in The Eternal Return of Fascism, a book that strips away the illusions of modern politics to reveal how fragile democracy truly is. Riemen reminds us that fascism does not arrive overnight, nor does it always come wearing the uniforms of the past. It returns subtly — through populist rhetoric, the erosion of truth, and the corrosion of civic virtue.

For me, this is not just a theoretical debate. The lessons of my father’s resistance in the Second World War, and the post-war struggle to build a democratic Europe, make Riemen’s words resonate with lived urgency. His reminder that democracy is not self-sustaining but must be continually defended is as relevant in today’s polarized and nationalistic climate as in the 1930s.

This note is both an endorsement and a warning: Riemen’s reflections art abstract philosophy but a mirror in which we must recognize our own time.

“Fascism is not dead. It sleeps beneath our feet, nourished by fear, resentment, and a hunger for false certainties.”

Among the many books left behind by my recently departed brother, I discovered a slim volume by Rob Riemen that reads like both a warning and a whisper from history: The Eternal Return of Fascism. Originally written in Dutch, the book is a passionate defence of humanism—and a plea to resist the forces of cultural and political decay that Riemen sees rising once more in our time.

Drawing from thinkers like Thomas Mann, Albert Camus, and José Ortega y Gasset, Riemen doesn’t just analyse fascism—he dissects it. Not as a political ideology per se, but as a spiritual void. A phenomenon born not of vision, but of resentment. Sustained not by reason, but by spectacle. Cultivated not by culture, but by the hatred of culture itself.

His words brought me back to my father, a man who had lived through fascism’s first incarnation in occupied Europe. “Fascism is like a weed in the garden,” he used to say. “It never disappears. It just waits.” He often quoted President Harry Truman:

“It is easier to remove tyrants and destroy concentration camps than it is to kill the ideas which gave them birth and strength.”

Those words echo with unsettling familiarity today.

Riemen’s later work, The Fight Against This Age, continues this meditation. He confronts populism head-on, calling it what it is: a modern form of fascism. Not in jackboots and uniforms—but wrapped in populist slogans, media complicity, and an utter disdain for thoughtfulness or truth.

In two essays—one historical, one fictional—he explores Europe’s failure to seize a spiritual opportunity in the 20th century and the question of whether the continent can still reclaim its lost nobility of spirit. The second piece, “The Return of Europa,” uses a philosopher’s journey to personify that very question: Will Europe once again embrace its humanist soul, or surrender it to resentment, fear, and tribalism?

“Will we accept the return of barbarism or fight for the rebirth of nobility of spirit?”

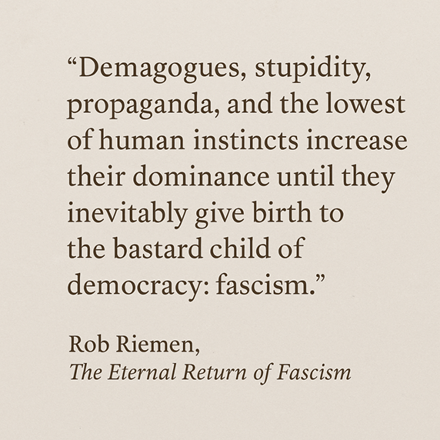

Riemen does not equivocate. For him, the bastard child of democratic decay is always fascism. He warns that:

To underscore his point, he cites Fellini, who observed:

“Fascism always arises from a provincial spirit… It cannot be fought if we don’t recognize that it is nothing more than the stupid, pathetic, frustrated side of ourselves… Latent fascism hides in all of us.”

This is not just political analysis—it is a diagnosis of the human condition in decay.

In Riemen’s view, fascism thrives in a vacuum of ideas. It is what remains when a society ceases to believe in anything greater than itself. Not progress. Not compassion. Not truth.

Despite the freedoms and material comforts of today’s Europe, we again find ourselves at a crossroads. Economic growth masks a spiritual erosion. Resentment festers. Elites either remain silent or, worse, play along—just as they did in the 1930s. The enemies of open society no longer need to storm the gates; they are invited in.

Geert Wilders. Marine Le Pen. Donald Trump. These are not defenders of “Christian civilization,” as they claim—but architects of division, merchants of fear, and enemies of the intellect.

His invocation of José Ortega y Gasset’s The Revolt of the Masses is particularly powerful. Mass culture, untethered from humanist values, becomes not a celebration of the common man, but a weapon against the very idea of excellence, decency, and self-restraint. In the 1930s, the cultural elite failed to confront fascism. Today, many intellectuals and journalists again look away—or worse, accommodate it.

In the Netherlands, Menno ter Braak diagnosed fascism as a doctrine of ressentiment—a nihilistic rebellion by those who feel wronged by modernity itself. We ignored him then. We ignore Riemen now at our peril.

Fascism, Riemen insists, is not simply an ideology. It is a spiritual disease. And as such, it must be fought not only politically, but morally. Culturally. Intellectually.

Even universities are not immune. Riemen chillingly recalls Mussolini’s Loyalty Oath for professors and draws a parallel to recent pressures on academic institutions in the United States, where truth is now contested not through argument, but through power.

His message is clear: if we want to defend democracy, we must fight for the human soul. Nobility of spirit is not nostalgia. It is resistance.

What We Choose to Defend

Rob Riemen reminds us that fascism does not arrive with fanfare. It arrives as a joke. A television personality. A populist slogan. A comforting lie told loudly and often. It seeps into our institutions, our language, our silence.

The task before us is not merely to condemn fascism once it takes power, but to recognize its signs long before. To reclaim a shared vocabulary rooted in truth, dignity, and humanism. To defend the life of the mind—while we still can.

These books are not manifestos. They are mirrors.

The solutions may be elusive. But the responsibility is ours.

Netherlands, WJJH – April, 2025

📌 Blog Excerpt:

Rob Riemen warns that fascism never truly disappears — it returns in new disguises: in populist slogans, in contempt for truth, in the decay of civic virtue. Democracy, he reminds us, is not self-sustaining. It must be defended again and again, or it will wither in complacency. His book is less a history lesson than a mirror — and what it reflects of our own time is deeply unsettling.