Rūmī : The Mystical Poet Across Time and Cultures

Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī—also known as Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Balkhī, Mevlânâ/Mawlānā (مولانا, “our master”), Mevlevî/Mawlawī (مولوی, “my master”), and more commonly as Rumi—was a 13th-century Persian poet, jurist, Islamic scholar, theologian, and Sufi mystic who lived in Konya, a city in the Ottoman Empire.

Three of the very greatest Persian poets flourished in his time, to be followed by a fourth a little later. Rumi was born in 1207, Iraqi in 1211, Sa’di sometime in the same decade, and Hafez a century later. As Michael Axworthy writes in “Empire of the Mind,” Iranians themselves normally consider Rumi, Hafez, and Sa’di to be (with Ferdowsi) the greatest of their poets. Iraqi is likewise an important figure, especially in Sufism. Together these poets represent the culmination of literary development in Persia since the Arab conquest.

Today, Rumi transcends centuries and cultures, and our understanding of him has evolved significantly. The question “Who is Rumi?” is complex and doesn’t yield a simple answer. The many roles attributed to Rumi—staunchly orthodox Sunni Muslim, closeted Zoroastrian, deviant Sufi, or someone too enlightened to subscribe to any religion—reflect the complexity of his identity. Some see him as a Khorāsāni, others as Persian or Iranian, while some insist he is Turkish. Despite our biases, what remains universally agreed upon is that Rumi left behind a legacy of poems exploring life’s profound questions. His message is timeless and universal, conveying deep truths through simple metaphors drawn from shared human experiences.

In our global village, it is fair to say there are at least two versions of Rumi—one in the West and one in the East. Ideally, these cultural perspectives can connect, allowing the essence, beauty, and emotional resonance of his poetry to be fully appreciated.

Rumi was born in 1207 in Balkh, modern-day Afghanistan, then part of the far eastern edge of the Persian Empire. At the time, the Persianate Empire stretched from India in the east to Greece in the west. The 13th century was a tumultuous period, with the Persian Empire mired in chaos and corruption, while the Mongol tribes under Genghis Khan moved westward, leaving destruction in their wake.

Rumi’s father, Beha-e Valed, a renowned religious leader, fell out of favor with the local rulers in Khorasan. Fearing the impending Mongol invasion, he gathered his family and followers and left their homeland, eventually settling in Konya, in the Sultanate of Rum (Anatolia, present-day Turkey), where he died in 1230. Konya was a cultural melting pot, where Rumi grew up in an environment of love, stability, and intellectual richness, following in his father’s footsteps.

Rumi enjoyed royal patronage and popular esteem, becoming an Islamic scholar and continuing a long tradition of theologians, scholars, and jurists. He taught Sharia, or Islamic law, and also practiced Tasawwuf, more commonly known as Sufism in the West. Sufism is a spiritual practice focused on understanding and drawing closer to God through the purification of the inner self, often through meditative chants, songs, and sometimes dance. Throughout his life, Rumi’s identity was deeply intertwined with his faith.

As he wrote:

“I am the servant of the Quran, for as long as I have a soul.

I am the dust on the road of Muhammad, the Chosen One.

If someone interprets my words in any other way,

That person I deplore, and I deplore his words.”

—Rumi (translated by Muhammad Ali Mojaradi)

Rumi’s magnum opus is the Masnavi, a 50,000-line poem written in rhyming couplets and quatrains that explores the mystical life and expresses a lifelong yearning to find God. Rumi advised readers of the Masnavi to perform ritual ablutions and be in a state of cleanliness, just as they would when reading the Quran or performing the five daily prayers. The intention was to connect deeply with the Creator. Other significant works include Fihi Ma Fihi, Divan-i Shams-i Tabrizi—a collection of poems dedicated to his spiritual mentor—and the prose works of the Discourses, Letters, and Seven Sermons.

The influence of Shams of Tabrizi, a wandering dervish whom Rumi encountered in 1244 at the age of thirty-six, left a lasting impact on him. “Jalāl al-Dīn,” wrote R.A. Nicholson in Rumi, Poet and Mystic, “found in the stranger that perfect image of the Divine Beloved which he had long been seeking.” Shams, nicknamed “the bird” for his restless nature, attracted attention for his wild demeanor, known for being blunt and antisocial. In Rumi’s household and among his circle, Shams caused discomfort, and Rumi’s pupils resented their teacher’s preoccupation with the eccentric stranger. They vilified and plotted against Shams until he fled to Damascus. Later, Rumi sent his son to bring him back, but the tongues of jealous critics wagged again, and in 1247, Shams vanished without a trace.

This encounter is often described as Rumi’s “spiritual awakening.” Shams’s presence shook the foundations of Rumi’s life, leading him down the path of love and mysticism. It is said that Shams introduced Rumi to the sema ceremony, the spiritual Sufi dance, also known as the Order of the Whirling Dervish, performed to the accompaniment of the lamenting reed pipe and pacing drum.

During the one to two years that Shams stayed with Rumi, upon his return from Damascus, Rumi married his 12-year-old stepdaughter, Kimia, to Shams. This was not uncommon at the time but was a remarkable event in Shams’s advanced life, with an unfortunate ending. For a while, the discomfort in Rumi’s circle ceased. However, a few months later, Kimia passed away due to illness, marking the end of Shams and Rumi’s companionship.

There are different accounts of Shams’s disappearance. History is unclear, but some suggest that Shams left Rumi in the dark of night and returned to his wandering days, with some accounts placing him in India. Another theory is that Shams was murdered by Rumi’s youngest son, Ala al-Din Muhammad, and his devotees in an honour killing for ruining Rumi’s reputation and causing Kimia’s death. Yet another theory attributes Shams’s disappearance to an assassination by devotees for blasphemy.

The agony of losing his friend overwhelmed Rumi, transforming him into the great mystic poet we know today. Streams of poetry flowed from his lips in praise of Shams, expressing higher truths and love. Rumi became a beacon of warmth and transformation, attracting people from all walks of life.

Rumi’s work is characterized by its lyrical beauty and exploration of spiritual longing. In his reflections on life, he often reminds us of the transient nature of our experiences and possessions—a poignant reminder to cherish the present moment and find contentment within ourselves rather than in external things. In the poem “The Guest House,” Rumi shares a deeper understanding of our place in the universe, encouraging us to embrace life’s ups and downs as valuable experiences and to welcome all emotions, even the negative ones, as opportunities for growth.

Yet, as Professor A.J. Arberry notes in his introduction to Mystical Poems of Rumi, poetry was far from the centre of Rumi’s life. Rumi himself appears to have been conscious of the elusive, evanescent nature of his utterances, as when he says in one of his poems, “My verse resembles the bread of Egypt—night passes over it, and you cannot eat it any more.”

Before anything else, Rumi was a learned theologian in the finest pattern of medieval Islam, deeply familiar with the Quran and its exegesis, as well as the traditional sayings of the Prophet Muhammad. His vast learning is reflected in his poetry, sometimes standing in the way of easy understanding and ready appreciation.

Rumi’s funeral in 1273 was attended by thousands of mourners from different cultures and nationalities, reflecting the cosmopolitan society of 13th-century Anatolia—a time when the cross-cultural exchange of ideas and arts flourished. He likened death to a wedding with eternity, famously saying, “Do not weep for me … Do not say how sad… To you, death may seem a setting… But really, it is a dawn.” In his own elegiac eulogy, he wrote:

“When you see my corpse is being carried,

Don’t cry for my leaving,

I’m not leaving,

I’m arriving at eternal love.”

—Rumi (translated by Muhammad Ali Mojaradi)

Afterthought:

In the West, Rumi is often presented as a secular, universalist poet. The first known translation of some of his work was published in 1772 by Sir William Jones, a British philologist, orientalist, and judge on the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William in Bengal. Persian was still the official language in Indian courts and public offices, a legacy of Mughal rule. Jones’s translation, published in 1782, influenced poets like Alfred Lord Tennyson and brought Rumi’s poetry to the attention of the Royal Asiatic Society and Victorian society at large. Jones’s most famous accomplishment in India was establishing the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784, reflecting his love for India and its culture, as well as his disdain for oppression, nationalism, and imperialism.

Rumi’s mystical allure attracted other British translators, including J.W. Redhouse in 1881, Reynold A. Nicholson in 1925, and A.J. Arberry, whose Mystical Poems of Rumi (1960–79) further popularized his work. However, Rumi reached global popularity in the 1990s, thanks to American writer Coleman Barks. More than seven centuries after his death, Rumi became a best-selling poet.

In the Muslim world, there is a valid complaint that Rumi has been “westernized” in the West, and liberties have been taken with the text to make the quotes flow better in English, risking straying from the original meaning. By downplaying or omitting Rumi’s orthodox Sunni beliefs, some translations have arguably distorted his message and erased the Islamic context from his work. Additionally, quotes attributed to Rumi are often inaccurately translated from Persian, removing references to his Islamic faith and culture. Interestingly, Coleman Barks, who played a significant role in popularizing Rumi in the 1990s, does not read Persian or Arabic but reinterpreted 19th-century translations for a mass American audience.

As Professor Franklin D. Lewis writes in the 2008 introduction to Mystical Poems of Rumi, translated from the Persian by Professor A.J. Arberry of the University of Chicago, “All English renderings will pale before the sheer beauty and sonorous intensity of Rumi’s original Persian.”

As Lewis notes, “Many who claim to ‘translate’ Rumi into English do not know Persian at all; their glimpse of Rumi, and the inspiration they receive from him, often rely on the pages of Nicholson and Arberry, or on English translations of Turkish translations of Rumi’s Persian.” Without the scholarly translations of Nicholson and Arberry, it would have been impossible for poets like Robert Bly and Coleman Barks to recognize Rumi’s potential appeal and reimagine him as a new-age American poet.”

WJJH – 8.9.2024

📌Blog Excerpt

Rumi, a 13th-century Persian poet, jurist, and Sufi mystic, holds a timeless and universal legacy through his profound poetry. His life was deeply intertwined with faith, and his encounters, particularly with Shams of Tabrizi, played a pivotal role in shaping his path of love and mysticism. Despite translations and interpretations, his original Persian work remains unparalleled.

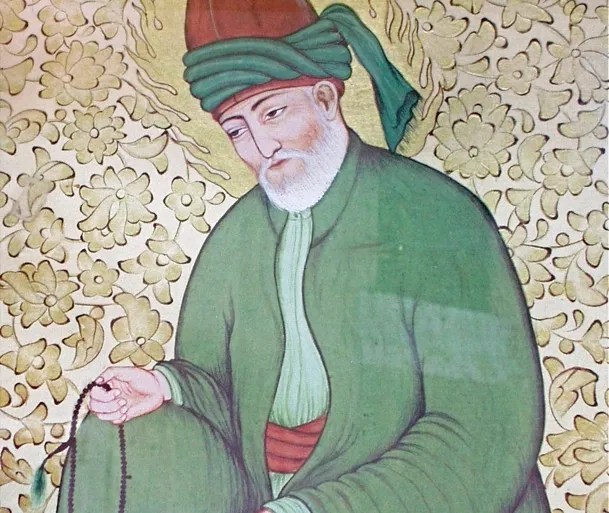

- Painted picture of Persian poet Rumi under glass on the outside the museum office at Rumi’s Mosque, Konya [Creative Commons]]

- Mevlana Rumi’s tomb in Konya is a point of pilgrimage for millions of devotees and tourists each year [Creative Commons]

- Mystical Poems of Rumi by A.J. Arberry (a new and corrected edition in one volume of Arberry’s translation of 400 ghazals of Rumi, with preface and notes by Franklin Lewis) (University of Chicago Press, 2009)

So informative I had no idea about so much of this… so enlightening .. thank you for the knowledge .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, much appreciated👌

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person