Reflections: The American Paradox

✍️ Author’s Note

✍️Writer’s Note

America’s strength has always rested on a contradiction — liberty and domination intertwined.

This essay explores how a nation born of freedom continues to wrestle with empire, and why moral renewal begins with honesty.

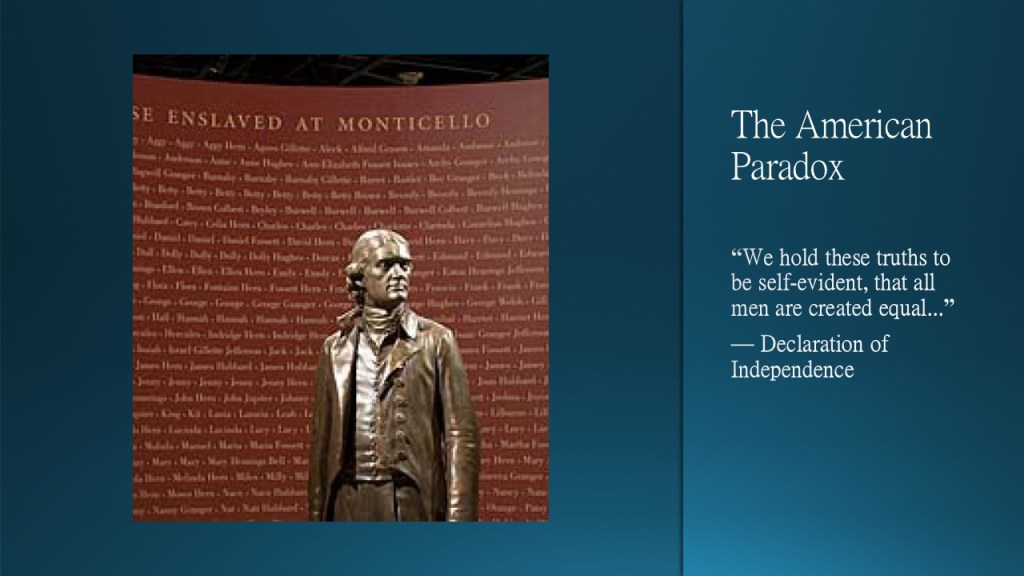

The American Paradox: Liberty and Slavery

From the nation’s inception, the American experiment has been marked by a striking paradox: the coexistence of Enlightenment ideals of liberty and equality with the brutal reality of slavery. Historian Edmund Morgan famously highlighted this contradiction, noting that the very figures who advocated for freedom and human rights—such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson—were themselves slaveholders. These leaders championed liberty, but their vision of freedom was often limited to white men, with African Americans and other marginalized groups excluded from those ideals. The rise of liberty from the 17th to the 19th century was thus accompanied by the rise of slavery, a system upon which much of America’s economic prosperity was built.

Slavery was integral to the production of crucial crops like tobacco and cotton, which fuelled both domestic economic growth and international trade. The Founding Fathers were able to preach the virtues of freedom while maintaining an oppressive system of forced labour because the economic benefits were too essential to sacrifice. This moral inconsistency became a core feature of early American society and continues to shape the nation today.

The Role of Civil Religion and “Manifest Destiny”

Despite the First Amendment’s establishment of a clear separation between church and state, the U.S. has long been a deeply religious society. The term “Civil Religion” has been used to describe a form of cultural nationalism that all Americans are expected to follow.

America, as a “creedal” society, is unified by certain principles embedded in foundational texts like the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

These documents—and the figures who drafted them—have been elevated to almost sacred status, turning Washington and Jefferson into mythical Founding Fathers and the nation’s core principles into articles of faith.

Abraham Lincoln, too, reinforced this narrative. During a period of great social upheaval and debate over the abolition of slavery, Lincoln argued that America had a sacred duty to preserve liberty and democracy, not just for itself but for the world. His belief that a common national faith would hold the nation together during the Civil War highlighted the paradox: the struggle for a nation to realize its own ideals of freedom while still allowing slavery to persist.

The doctrine of “Manifest Destiny” further complicated the American Paradox. Alongside the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which asserted that the Western Hemisphere was no longer open to European colonization or interference, this ideology became the rationale for U.S. territorial expansion and imperial ambitions. It justified wars and interventions, from the Spanish-American War to the imperialist pursuits of the early 20th century. Upon assuming office in 1901, Theodore Roosevelt inherited a burgeoning empire and thrust the United States onto the world stage as a significant actor in power politics. As Joseph Nye observed, Roosevelt was the first president to deliberately project American power globally.

Roosevelt revolutionized U.S. foreign policy, asserting that Providence had entrusted America with a unique role as both guardian and evangelist of Western civilization. He believed that a strong foreign policy serving national interests was not only a duty but a means to uplift those deemed incapable of self-governance. This perspective echoed the British imperialist view of spreading civilization, encapsulated in Rudyard Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden.” Roosevelt’s intervention in Latin America, particularly in the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Cuba, and his involvement in the Philippines underscored this self-serving yet idealistic approach. His interventions often aimed to protect U.S. commercial interests and extend American influence under the guise of benevolence.

Woodrow Wilson later invoked the doctrine of “Manifest Destiny” to promote his vision of making the world “safe for democracy,” and Franklin D. Roosevelt similarly leveraged it during World War II to galvanize the American public against the Axis powers. Together, these leaders’ actions highlight the enduring influence of Manifest Destiny and its complex legacy in shaping U.S. foreign policy.

More recently, George W. Bush invoked this sense of divine American mission to justify military intervention in Iraq, and Joe Biden echoes similar themes in the U.S. support for Ukraine. This underlying belief that the U.S. has a unique destiny to lead and protect liberty worldwide often leads to foreign policy choices steeped in hubris, rather than humility.

Persistent Contradictions in Modern Society:The paradox extends beyond America’s history of slavery and imperialism. Even today, the nation grapples with contradictions between its ideals and realities. The persistence of capital punishment and the lack of effective gun control legislation are stark examples of these internal inconsistencies. In a nation that holds liberty and the sanctity of life as core principles, the continued use of the death penalty and the prevalence of gun violence represent ongoing tensions in the fabric of U.S. society.

The American Paradox, in both its historical and contemporary forms, raises fundamental questions about how a society that champions freedom can reconcile the contradictions that undermine those very ideals. This paradox is not unique to the past; it continues to shape America’s internal struggles and its approach to world politics. The challenge, moving forward, is whether the U.S. can align its actions with its principles, acknowledging these moral inconsistencies with the humility necessary to avoid the pitfalls of hubris.

Missed Post-Cold War Opportunities and Strategic Failures

In the 1980s, Russia and the global order were greatly influenced by Mikhail Gorbachev’s efforts to reduce Cold War tensions and reform the Soviet Union through Glasnost (openness) and Perestroika (restructuring). Gorbachev’s aim was to introduce democratic governance, a freer civil society, and the rule of law. He briefly gave Russia a glimpse of democracy, a vision that had emerged only fleetingly in 1917 before being smothered, as it would be again in the 1990s and beyond.

The end of the Cold War offered the United States a rare opportunity to reshape global security and foster international cooperation. However, the antagonistic roots of U.S.-Russian relations ran deep, going back to the post-1947 “containment” doctrine, which sought to encircle and limit Soviet power.

This strategy, championed by George F. Kennan in 1946, discouraged collaboration and embraced military encirclement. Kennan once observed that even if the Soviet Union were to disappear, the U.S. military-industrial complex would find another adversary, as disarmament would be too disruptive for the American economy.

The years of change between 1989 and 2001 saw collaboration between George H.W. Bush and Gorbachev, culminating in the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START). Gorbachev, a decent man in a country that often equated decency with weakness, was instrumental in ending the Cold War and allowing the democratization of Eastern Europe and the independence of the Baltic and Caucasian states. However, Gorbachev was overtaken by events, and after the failed 1991 Soviet coup, Boris Yeltsin emerged as the first president of the Russian Federation.

The Yeltsin years, marked by political and economic turmoil, saw Russia once again hijacked by vested interests, leading to widespread disillusionment. The rapid reunification of Germany further strained the situation, with the West missing an opportunity for strategic realignment with Russia. For Russia, the dissolution of the Soviet Union left deep emotional scars, fuelling feelings of humiliation and resentment. Marginalization in international institutions, coupled with a perceived lack of respect from the West, exacerbated these wounds.

Despite early attempts to integrate Russia into the global economy, the West failed to forge a long-term partnership with Russia. Instead, the U.S. and Europe treated Russia as a peripheral player, a decision that contributed to the breakdown of democracy in Russia and the rise of authoritarianism. The early 1990s presented a chance for a new world order, but the momentum for close cooperation with Russia was lost with NATO’s expansion eastward in 1998.

As the European Union began its post-1992 Maastricht Treaty reforms, there were genuine attempts to build a prosperous Europe that could have included Russia. However, arrogance from both Europe and the U.S. alienated Russia, squandering the opportunity to establish a lasting partnership. Instead, Russia chose isolation, leading to further decline.

The enlargement of the European Union, particularly its rapid expansion into Eastern Europe, often appeared to serve U.S. interests more than those of Europe. Zbigniew Brzezinski observed that this enlargement expanded U.S. influence within the EU without fostering a politically integrated Europe capable of challenging American dominance.

This is a result, the pursuit of a more cohesive European Union was put on hold, and Europe missed the opportunity to pursue greater strategic independence at a crucial moment in history. A more prudent approach could have been a “two-speed” Europe, where Western European nations would focus on deeper integration, while Eastern European countries were gradually incorporated. This would have helped protect the foundational values of the EU while managing the complexities of enlargement more effectively.

Today, we witness deep cultural and political divides within the EU, particularly with the rise of illiberal democracies in parts of Eastern Europe, where media freedom, judicial independence, and human rights are increasingly undermined. Europe’s reliance on the U.S. for defence and foreign policy—especially regarding Israel, the Middle East, and China—has further diminished its geopolitical standing and undermined its ability to act as an independent global power.

After Gorbachev and Yeltsin, Vladimir Putin emerged as a pragmatic, yet increasingly authoritarian, leader. Putin’s cold-eyed cynicism, combined with Russia’s marginalized role in the international system, has shaped Moscow’s confrontational stance.

The U.S.’s post-Cold War policies, particularly under George W. Bush, exacerbated these tensions. Bush’s selective multilateralism, coupled with wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, undermined international institutions like the United Nations and the International Criminal Court. His reckless push for NATO expansion to include Ukraine and Georgia at the 2008 Bucharest Summit was seen as provocative by Russia, leading to the 2008 Russia-Georgia War. This NATO overreach contributed directly to today’s confrontations, including the ongoing crisis in Ukraine.

The Iraq War marked a turning point in global perceptions of U.S. leadership, eroding its moral authority. The Bush administration’s actions began the decline of Western dominance, which had lasted for centuries. NATO’s continued expansion and the U.S.’s unwillingness to address Russia’s security concerns have since fuelled revanchist sentiments in Moscow.

George F. Kennan, the architect of America’s Cold War policy, had warned against NATO expansion as early as 1998, predicting it would lead to a new Cold War. Kennan’s warning went unheeded, and NATO’s encroachment on Russia’s borders stoked feelings of betrayal and hostility.

The failure of U.S. foreign policy after the Cold War lies in its missed opportunity to foster a more cooperative international order. Rather than adapting to a multipolar world, U.S. leadership clung to Cold War-era strategies of military supremacy and interventionism, from Somalia to Iraq. The aggressive expansion of NATO, coupled with a failure to build an inclusive security framework, alienated Russia, contributing to the simmering tensions we see today.

These decisions were not just tactical missteps; they were strategic errors that continue to shape the global geopolitical landscape.

Present-Day Divides: The Costs of Primacy and Military Overreach

The doctrine of American Primacy finds its roots in political theories that span centuries. From Hobbes’ views on authority to Metternich’s balance of power, George F. Kennan’s containment strategy, and the power preponderance theory championed by scholars like Stephen Brooks and William Wohlforth, these ideas collectively defend the notion of U.S. hegemony. If, as proponents argue, power preponderance ensures peace, then American military dominance is not just in the interest of the U.S., but in the interest of the global order itself.

However, the pursuit of American primacy has profoundly affected the fabric of U.S. society. Early cracks in this facade appeared with the Bay of Pigs and deepened through Vietnam, culminating in Iraq and, most recently, the proxy war in Ukraine. Each conflict has further strained the nation’s social cohesion, with lasting repercussions that will be felt for decades. America is now a country deeply divided, overstretched both militarily and financially.

Since the 1960s, beginning with the divisions sparked by Vietnam, the U.S. has been grappling with mounting injustices, societal paralysis, and widening inequality—all exacerbated by global military engagements. The burdens of global leadership have weighed heavily on America’s domestic landscape, as foreign interventions proliferate while social and economic fractures widen at home. Addressing these challenges is crucial if America is to restore itself as a more egalitarian society.

The U.S. faces a multitude of structural problems, including a broken education system, immigration reform challenges, failing infrastructure, rampant gun violence, overcrowded prisons, an inadequate social safety net, and the absence of universal healthcare.

These issues demand urgent attention, particularly as the nation continues to grapple with the economic consequences of unnecessary wars and a growing national debt. Moreover, these challenges unfold against the backdrop of environmental crises and global warming, adding yet another layer of complexity.

The disconnect between American leadership’s aspirations and the lived realities of its citizens is growing. A sizable portion of the population feels left behind or unable to adapt to the demands of modern society, contributing to daily struggles that are becoming increasingly untenable. Mounting national debt, deteriorating infrastructure, and rising income inequality underscore this divide.

Populist sentiment is on the rise, reflecting a desire to withdraw from costly international entanglements in favour of addressing urgent domestic needs. In many cities, the disappearing middle class and the deep-rooted inequality issues compound the problem.

Historically, great powers facing military overextension often experience economic and political erosion. America is no exception. Repositioning the country to correct these imbalances presents an opportunity for renewal. Failure to do so will only perpetuate divisions, injustices, and paralysis, pushing the nation closer to a breaking point.

The pursuit of global primacy has become unsustainable, financed largely through debt and the exploitation of global resources. The costs of foreign interventions are now felt at home—manifesting in political polarization, economic stagnation, and growing public disillusionment with America’s role in the world. As Lord Palmerston famously observed, nations have “permanent interests” rather than permanent allies. The pressing question for the U.S. today is not just how to remain a global leader but whether it can reconcile the demands of leadership with the urgent needs of its own people.

The assumption that U.S. primacy is both desirable and achievable is increasingly dubious in a world where power is more evenly distributed, and America’s reliability on the international stage is frequently questioned. U.S. leadership must be redefined, recalibrating vital national interests in light of past failures, shifting global dynamics, and growing internal demands.

Former Secretary of State James Baker noted in his political memoir: “Effective U.S. leadership often depends on the ability to persuade others to join us so we can extend our influence. To build a coalition, a diplomat must appreciate what objectives, arguments, and trade-offs are important to would-be partners.” The U.S. must now embrace this more nuanced approach if it is to regain its standing both at home and abroad.

Conclusion: Rethinking Global Leadership

As we grapple with the paradox of American leadership—internally divided and externally overextended—it becomes increasingly evident that a new course is necessary, one that moves beyond the waning premise of global primacy. This path should not be defined by unilateral dominance or interventionism, but rather by humility and partnership.

The current trajectory, marked by the pursuit of dominance and interventionism, is precarious. The ideological battleground of democracy versus autocracy threatens to plunge the U.S. into a Thucydides trap, risking a catastrophic conflict with both China and Russia. The prospect of tactical nuclear weapons is no longer unthinkable in this environment, where both sides dangerously assume the other is bluffing. The persistence of “endless wars” feeds a cycle of hubris, with Nemesis inevitably following.

In the name of its Manifest Destiny, the U.S. has often pursued hegemony through a self-serving interpretation of international law and militaristic strategies, as seen in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. These interventions have destabilized the global order, underscoring the need for a new equilibrium, one grounded less in Wilsonian idealism and more in the pragmatic approach of the Kissinger era. Recent conflicts—Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s military actions in Gaza—have further exposed the fragility of global stability.

With the brief unipolar moment now behind us, the world has transitioned into a multipolar reality. Powers like China, Russia, and their allies are challenging the Western-dominated order, resisting the expansion of U.S. alliances. This shift necessitates a rethinking of U.S. global leadership and a more nuanced approach to international relations.

While the United States positions itself as a champion of democracy, freedom, and capitalism, it must also confront its own internal challenges—deepening inequality and political division. Promoting human dignity and political rights globally is laudable, but a sustainable foreign policy must strike a balance between moral imperatives and national interests. Acknowledging the cultural and historical contexts that shape values across different societies is crucial to fostering a more adaptable and respectful U.S. foreign policy—one that recognizes the diversity of human experiences and aspirations.

Navigating the complexities of a multipolar world requires a strategy rooted in realpolitik and cooperation. Despite its theoretical opposition to spheres of influence, as Graham Allison points out, the U.S. has de facto accepted many such spheres in the 20th and 21st century. This recognition calls for a more pragmatic foreign policy—one that tolerates a diffusion of power.

In the wake of the unipolar era, the U.S. must consider a new model of leadership rooted in primus inter pares (first among equals). This approach would emphasize shared responsibility in addressing global challenges. Prioritizing diplomatic solutions over military intervention, building consensus, and respecting international law and institutions are crucial steps toward promoting global peace and stability. However, such a shift would require political will—both domestically and internationally—that may not currently exist.

The world is at a pivotal juncture, facing existential threats like climate change, pandemics, artificial intelligence, and nuclear proliferation. These global challenges demand collaborative efforts that transcend regional conflicts and prioritize the survival and well-being of humanity.

Given the rise of populist nationalism and political malaise, a model of shared responsibility could attract both international and domestic support. It could also help the U.S. rebuild bipartisan consensus while addressing its own structural issues—revitalizing democracy and reinforcing its domestic foundations.

The erosion of national sovereignty and the weakening of non-interference principles further highlight the need to reevaluate the current rules-based order, which is now in disarray. With the rise of China and other influential powers, global governance must evolve to become more diverse and flexible, accommodating shifting power dynamics.

Reforming international institutions, particularly the United Nations—where veto power gives disproportionate control to the five permanent members—is essential. This imbalance has allowed nations like Israel, with U.S. support, to disregard numerous UN resolutions. China, advocating for reform, has argued that the international system must be updated to reflect modern power realities and promote global inclusivity.

Ultimately, only by aligning its ideals with its actions can the U.S. navigate the complexities of an emerging multipolar world. By doing so, it can ensure that the values it professes—liberty, equality, and democracy—are not undermined by the contradictions of its past.

William J J Houtzager, Aka WJJH- November 2024

📌 Blog Excerpt

The American Paradox illustrates the tension between ideals of liberty and the historical reality of slavery and imperialism, from founding figures to contemporary foreign policy. The U.S. struggles with moral inconsistencies, questioning its global leadership amidst societal division, military overreach, and pressing domestic issues that require urgent resolution and a shift towards cooperative international relations.

Good summary og US history and where se are today. Future looks uncertain and hard to predict.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Much appreciated for your kind comment. When growing up I was blessed with a excellent history teacher who taught us to look at the connection and the past can teach of much about understanding today and the future. Time will tell, but I am not optimistic about the former and future guy, as he already showed who he is.

LikeLike